When the Whole Earth Catalog, with the Apollo photograph of the Earth on its cover, appeared in the fall of 1968, it reordered the worldview held by much of my generation. That photo, at a glance, made it obvious that all of us had a shared destiny but our resources were finite. Stuart Brand, a Veteran and Stanford-educated biologist, who was also a Merry Prankster, was its editor. It was 64 pages long and sold for five dollars – everyone I knew was reading it. It was an embryonic internet search engine (think of it as the web’s wood-burning era) offering “access to tools”– a broad definition that included practical skills, scientific knowledge, and metaphysical commentary.

Donner Summit

Many of us were starting families at the time and the world seemed like it was in turmoil. In 1969, when we began looking for rural land, gold reached a record high of $47 per ounce, Neil Armstrong stepped onto the Moon, the Woodstock Music and Art Fair opened in upstate New York, and the Manson family committed the Tate-LaBianca murders. In that same year Richard Nixon was inaugurated president and Golda Meir became Israel’s prime minister. On Vietnam Moratorium Day, millions nationwide protested the war. In Greenwich Village police raided the Stonewall, a gay bar, causing hundreds of patrons to riot for three days. In November Alcatraz Island was seized by militant Native Americans and in December 300,000 people traveled to Altamont to see the Rolling Stones. Meanwhile, Britain abolished the death penalty and the Jackson Five made their first appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show.

We were convinced that if we would just get back to the land, we could cultivate a natural lifestyle, which we imagined would be peaceful and just. The Whole Earth Catalog, with its mix of practicality, cross-cultural reflections and rootsyness, was the ideal handbook. It helped by providing some practical instructions and possibilities about creating community.

COLONIZERS

There it was, on the first page: “We are as gods and might as well get good at it.” We believed that, and lo, we were arrogant. The truth is that, for the most part, we acted more like colonizers than guests. Critical of the local population, we thought that the existing logging, mining, and grazing practices were unnatural, immoral even, and we were outspoken about our beliefs. Needless to say, it’s difficult to make friends when you’re so judgmental up-front – we soon found that they held strong beliefs, and opinions, too.

We really thought we were onto something special, or, more accurately, that we were special—after all, this was the Age of Aquarius. While there were many people around with high ideals about community and equality, there was also the persistent temptation to wallow in personal freedoms such as alcohol, drugs, and sexual experimentation (no judgment here). Despite high-minded hippie rhetoric, there was often a huge spoonful of self-indulgence in the mix. I bring this up because that’s the way I was when I moved to the foothills of rural California.

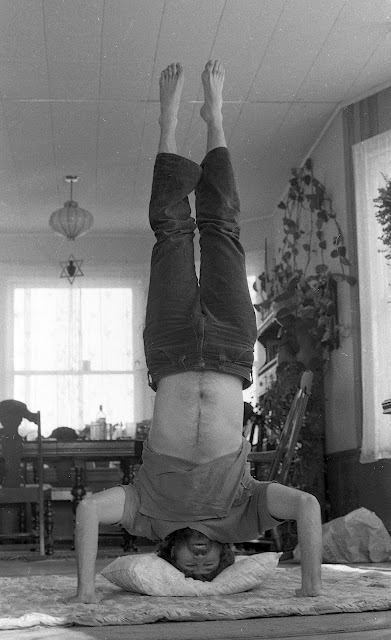

Woody

We were reinventing ourselves, which was not a new concept in California. It also happened during the gold rush, when a sailor from Maryland shoveled alongside a lawyer from New York. Your background didn’t matter; in those days “a man was measured by the size of his pile.” Of course, the fundamental difference between 1849 and 1969 was the motive. One was about accumulating wealth and the other was about social evolution.

We borrowed freely from other traditions, mixing and matching to create the eclectic look and philosophy that was (and is) so easy to ridicule by contemporary journalists. Mongrelized hippie culture included idealized Native American rituals, mantras from Tibet, fringed buckskin bags, sandals from Mexico, long hair, and beads. Women wore huipils from Guatemala and bedspreads from India, while men fetishized denim and working-class attire. In our search for authenticity, we mail-ordered Amish and “plain clothing” from the family-owned Gohn Brothers store in Middlebury, Indiana. For a while we equated severity with serenity and spirituality. Most of us felt there was some inherent righteousness in doing things the hard way; there was little discussion about convenience or “time saving.”

NOVICE/INITIATE/GUEST

When we bought land, we had no idea that the simple life required so many chores. We had to learn to fix our roads, learn basic plumbing maneuvers, acquire carpentry skills, troubleshoot the generator, put up the tomatoes, fill the kerosene lamps, attend school board meetings, and split wood – then do it over again. We added to our toolboxes, we learned to do new things and we all became more self-reliant. There’s a lot to be said for self-reliance. By that I don’t necessarily mean proficiency in a particular skill so much as a general attitude that we can make it work. I find that, even today, many of my back-to-the-land-era friends radiate an inner resilience and confidence and handle change well.

To live in a rural area, you need to know your neighbors. You’ll meet them eventually – perhaps in a snowstorm or fire. Our neighbors, some of whom had been living here for many generations, taught us sensible things. In time we learned some respect for the hard work that lumbermen, cattlemen and truck-drivers do, and respect for the women who ran households, who seemed to know infinitely more than us and were often more clever and witty than our college-educated friends. We even appreciated the (formerly) “dumb-ass” teenage neighbor who assembled the ram pump while we fumbled with the instructions.

At home there were more than enough tedious and very unromantic chores to deal with. The work was often repetitive and not too stimulating, but you were not alone in your madness because it was a shared ethos. It could also be idyllic. Neighbors, especially from your own tribe, were usually eager to pitch in because workdays would end with a sumptuous feast, music, stimulating conversation, play, good smoke, and laughter – family fiestas, really.

Many members of our community pitched in to help build a new elementary school. Part of the project included the first log cabins on a public-school campus since the state began supervising school construction. The trees were felled with crosscut saws then hauled with muscle and log carriers. Logs were limbed with axes, peeled with spuds and drawknives, and their butt ends trimmed with chisels. An eight-woman crew “chinked” the interior space between logs with saplings, a tedious job requiring skill and finesse. The two log cabins had to be designed and built to meet earthquake safety standards. This required the insertion of vertical rebar to pin each course of logs to those below it. We delighted in the increased safety without having to add visible, nontraditional bracing on the logs.

Jonathan

I’ve forgotten how we explained our rationale to the school superintendent’s office, but from here I can see we did it for the joy of it—the deep pleasure of physical work, camaraderie, learning, and visible accomplishment. There was a lot to learn and initially I felt that I had nothing much to contribute. It’s very humbling to realize that you have no usable skills, despite your precious “education.” To get by, you needed to achieve a certain level of competence at something practical. When you reached the point where you couldn’t leave home without a pocketknife, you were approaching a level playing field with your “redneck” neighbors. Your worth was based on what you did and how well it was done, and not on your “vision” or fantasies. It took a while to see that the ecology of a place includes the human population as well. In the 1970s Gary Snyder wrote a poem entitled “Why Log Truck Drivers Rise Earlier Than Students of Zen,” which is, itself, a poem, or at least a provocative question. At the time, the Pine Cone Cafe in Grass Valley, and several other local places that served breakfast to loggers, opened at 3:30 a.m.

LEARNER/OCCUPANT/NEIGHBOR

The concept, or notion, of right livelihood offers the possibility that you can make a living by using your talents (whether innate or acquired). It gets a bit tricky because there are mountains and valleys (learning and desperation) on this path, but it is possible with humility, hard work, humor, and blind faith. So, if you wanted to stay here, you decided to either pursue your dream/lifework and hope that it would support you, find a “real” job and move to where the money was then return with some, or simply move on.

Earning money was a serious problem. We needed it for food and land payments. In our neighborhood there were a few jobs with the schools, for instance teachers, teacher’s aides, maintenance, and kitchen help. Some commuted the 20 miles to the nearest town for whatever work they could find there, and there was also the National Forest, which had some seasonal forestry-oriented work. Others of us, men and women, formed crews and bid on seasonal contracts with the Forest Service and timber companies. We fought fires, climbed trees to gather pine and fir cones for seeds, planted trees, thinned tree plantations, and built trails. As we became more proficient, we sometimes moved to distant locations where we worked long hours for weeks at a time. On all of these jobs, you were paid for what you produced. If you were good, you could make some decent money. It was hard work, but there is incalculable value and worth in a good day’s work. When we returned home, fit, honest and dirty, with a pocket full of cash, we felt like working-class heroes. Somewhere along the way, what was once a groove became a rut. This kind of work was perfect for a while, but it was not intellectually engaging and not everyone was happy with the physical demands.

There were those among us who believed that a spiritual path was the way and that the details would take care of themselves. Most of these people lived very simply, already had money, or grew marijuana. You had to lean into your dream and try to make it happen, which many people attempted and succeeded at. Flirting with animism, exotic religions, and pious posturing didn’t really change much. My friend Will Staple nailed it in his poem “Eastern Mysticism”:

What good did getting up

Every morning at 5:30 to

Meditate do?

Your girlfriend

Left you.

When I lived in San Francisco I was a social worker and a photographer for alternative newspapers, but here in the hills I worked at forestry-oriented jobs, hammered nails, mixed concrete, and found occasional photography gigs illustrating articles for writers who were also struggling.

In the mid-1970s the Forest Service began implementing the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA). That legislation recognized our cultural heritage (historical and archaeological sites) as resources to be protected. I had a degree in anthropology, so I was hired, as part of a team, to locate, record, and manage these sites on public land. At the time this was a dream job, as I was being paid to explore the landscape (in a reliable truck, no less) while learning more about its culture and ecology. Another benefit was working with wildlife biologists, botanists, hydrologists, foresters and geologists and learning something about their perspectives. In time I became proficient with map and compass, made new friends of all sorts, and became a competent guide in remote regions. But working for the government has its peculiar limitations, and eventually, after 12 years, it was time to move on.

Susan

Meanwhile I was immersed in my watershed, its function, and its recreational and spiritual possibilities. In an attempt to share our enthusiasm, my lovely late wife Susan and I, self-published a trail book in 1993. It was heavy on history and personal adventures and it was very well received. Today I still enjoy learning more about hiking, photography, and writing. Miraculously, this focus has become my vocation and generates enough income for me and my family to live simply, but well.

ELDER/ADEPT/HOST

Contrary to the common stereotype, most of us were not “dropouts.” By the mid-1970s we were rooted in the community and active in local and regional politics. We voted and put people on school boards, on the County Planning Commission, on the California Arts Council, in water-managing agencies, on fire departments, in cultural centers, and even on the county Board of Supervisors. We established prestigious nonprofit agencies. We were very active in the arts with nonstop music, theater productions, publications, dance recitals, rowdy poetry readings, performance art, and exhibitions of all sorts. I feel that we have contributed vitality to the local culture without sacrificing worthwhile traditions. In doing so we’ve been respectful, sometimes outrageous, but always civil.

More than 25 years ago, while enjoying a local function featuring Native American traditional practices, I was asked to set the tone for the day with an opening statement. I was surprised by the request because I really didn’t see myself as an elder. For one thing, I was intimidated by the presence of “real” Indian elders. Also, my personal vanity wouldn’t allow me to recognize my age, status, and responsibilities. It only recently dawned on me that, despite my reluctance and many flaws, I’ve become an elder anyway. Looking back, I can see that personal growth is a slow and steady process, like wood growing in trees.

Being an elder carries responsibilities. Like it or not, you become a grandparent-at-large. It matters when you speak up in public (hopefully, less often but more judiciously). Public approval and disapproval matter, and, if you have credibility, you are listened to. It goes without saying that whatever behavior earned you your good reputation should be sustained. Maintain a sense of humor. Offer advice when it’s requested but realize that you do have the benefit of a long-range perspective and have seen the consequences of past visions and decisions. Finally, where and when it’s appropriate, share the knowledge and the stories that you’ve spent a lifetime accumulating.

Unnamed Pond / North Yuba

• • •