|

| Hydraulic mine waste released into the Yuba River, Sierra Nevada, California, 1867 |

Our little town, “a great place to live”, is now a heavily marketed tourist destination. There are frequent year-round events to attend and lunch will easily cost you $20 plus. Locals, unless they own a business here, don’t go downtown much. Stores and restaurants open and close at about the same rate they did during the gold rush. Business is certainly legitimate, but the link between greed and gold is another story altogether.

For the last 40 years I’ve researched documents and books about gold mining in the north central Sierra Nevada. I’ve located and recorded gold mining sites and seen their legacy first-hand – it’s time to honestly assess the benefits gained by a few at the expense of local degradation and anthropogenic havoc to the environment. Because the topic is huge, I’m focusing on hydraulic mining and its infrastructure, an engineering tour de force, but an environmental catastrophe, one that we’re still dealing with today.

In the latter half of the 19th century the ideology of self-aggrandizement and laissez-faire capitalism legitimated, even encouraged, the single-minded pursuit of wealth at all costs and thus made many people susceptible to gold fever. A quick look at Google shows at least 16 books with Gold Fever prominent in the title – I’m sure there are more, as well as hundreds of newspaper and magazine articles. In addition to Charlie Chaplin’s classic 1925 film The Gold Rush, filmed at Donner Pass, near Truckee, California, the two other films about gold mining that attracted popular attention were The Treasure of The Sierra Madre (1948) and Paint Your Wagon (1969).

The Treasure of The Sierra Madre featured a speech about gold fever written by John Huston who also directed. It’s a wonderful film starring Humphry Bogart as Dobbs, Walter Huston (John Huston’s father) as Howard and Tim Holt as Curtin. The speech was delivered, with authority, by Howard the perennial prospector, and here are a few lines:

“But I tell you, if you was to make a real strike, you couldn't be dragged away. Not even the threat of miserable death wouldn't keep you from tryin' to add $10,000 more. $10,000, you'd want to get 25. $25,000, you'd want to get 50. $50,000, a 100. Like roulette. One more turn, you know, always one more ... I’ve seen what gold does to men’s souls.”Then in 1969 came Paint Your Wagon, a campy Hollywood musical, based loosely on You Bet, a former hydraulic mining town in the upper reaches of the Bear River in Northern California. This has been a favorite play for amateur thespians in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada for decades now and it is always performed with exuberance and joy. Clint Eastwood sings the last song of the film, Gold Fever. It hints at the obsession, and the strung-out delusional quality of gold fever when Clint sings, “Gold, gold, hooked am I – Susannah, go ahead and cry.”

These three films have helped create a superficial awareness of gold mining in the popular imagination. Most history buffs and casual readers don’t care much about the actual history and consequences of gold mining, but they love the stories, both factual and those made-up from a few strands of truth. It’s difficult for the reader to distinguish between the two, nor do they necessarily care to. They want entertainment. The late Ken Kesey, author and a historical figure himself, acknowledged it: “To hell with facts! We need stories.” Perhaps we will eventually present history with a human and an environmental perspective – stories that engage the imagination and educate, or at least raise awareness? A good example of a history-based genre blending book is Shirley Dickard’s, Four Women, for the Earth, for the Future (2020).

Here in Nevada City, a former gold mining town located on Deer Creek, a tributary of the Yuba River, The Diary of a 49er by Chauncey Canfield (1906) is usually the first sampling of local history that newcomers to the area read. The book is actually a fictional diary of Alfred T. Jackson, during his days as a gold miner from 1850-1852. Canfield was a journalist with some grasp of local history and geography, but it’s no more than an entertaining story that gives some feel for mining communities in the northern mines of the Sierra Nevada in the mid-19th century. It’s not history, but it is appealing and entertaining. There are far better reads, like Louise Klappe’s Dame Shirley’s Letters and John Borthwick’s 3 Years in California, both of which are based on first-hand observations and are full of engaging stories.

Another story that's in constant flux and modified in every telling, is the story of Josefa Loaiza (aka “Juanita”) who, in 1850, defended herself and killed a drunken white man in the process. She was the first woman hanged in California, and the hanging was condoned by a lynch mob. In the confused “ethics” of the overwhelmingly male crowd it’s possible that, had she not been a Mexican woman, she may not have been hanged. Racism was rampant. The story of Josefa is a rich tale with several sub plots that’s been told over and over so that, if you compare a few versions, you can see the dynamic of storytelling and how in each round of telling it is subtly reshaped by the teller. This will continue as long as the story is told (See my blog entry for June 28, 2019).

Major Downie, in his reminiscences (Hunting for Gold) cites part of the Downieville – Goodyears Bar mining code: “… none but native and naturalized citizens of the United States shall be allowed to hold claims” and “that the word ‘native’ shall not include the Indians of this country.” Well, what about the native Nisenan people who cared for this ecosystem for centuries? They were hunters and gatherers who were aware of gold, which was not scarce, but found it useful only as net weights and throwing stones.

Imagine this: Is it possible that in places where the streams ran wide and shallow, with their gravel beds clearly visible (the same places that salmon prefer for their redds), when the sun was low in the sky, might the sun have reflected the visible placer gold in the gravel causing the streams to glow, or at least glitter? It’s my fantasy and it may have been shared by many miners, however, except for a few, they got here too late. If it actually happened, the Nisenan enjoyed sparkling streams for centuries prior to the gold grubber’s arrival.

Appreciation of hunting-gathering lifeways by archaeologists and anthropologists changed substantially in the late 1960s and continued at an accelerated pace into the present. Hunter-gatherers are now more commonly seen as master ecologists, people with sophisticated relational social structures and advanced interactive environmental strategies. They had a sophisticated, specific and intimate relationship with the land upon which they lived, and still do. This kincentric orientation is based, not on child-like instinctual/quasi-mystical interaction with their natural surroundings, but on acute observation of the environment, which is recognized as part of an integrated whole. In hunter-gatherer cultures knowledge about the environment is transmitted from generation to generation over thousands of years, resulting in a detailed corpus of vital environmental knowledge and extremely successful economies.

Gold mining is gambling. Victorian white men, at least those invested in middle-class values, had some difficulty accepting mining as a proper profession. It was rough, dirty work characteristic of the working class and secondly, they questioned their ability to handle the physical work and extremes of weather. Mining required a transformation in values and a return to brutish behavior. Those who felt guilt about leaving their families or had some reservations about the pursuit of wealth for its own sake, could calm their anxieties by trusting in the ethnocentric concept that they were serving the higher purpose of fulfilling the nation's Manifest Destiny.

Miners feverishly looked to new technologies to make the task of moving the earth easier and producing more profit. There were constant innovations – some ideas worked, and some didn’t. One invention, or insight, that did work was the application of pressurized water against an auriferous bank, collapsing it and performing the work of many men with hand tools. It was called the hydraulic process. Hydraulic mining’s impact is still with us although many people think that the problem ended with the Sawyer Decision of 1884, which is often described as the “first environmental legislation.”

Judge Lorenzo Sawyer, who wrote the Sawyer Decision, was once a gold miner in Nevada City himself. When he arrived in December of 1850 he wrote in his diary, “Beauty, grandeur, sublimity characterize every lineament of this vast scene.” But as he looked closer, he noted:

“Deer Creek, Little Deer Creek, Gold Run, and many others, see their beds to a great extent thrown up, behold the pine, the fir, the cedar, the oak, these monarchs of the forest undermined, uprooted and for a long distance piled upon each other in the utmost confusion – this is the work of man. Again, cast your eye along that broad belt of earth newly thrown up extending five or six miles along the base of the mountains, observe the thousands of shafts sunk deep into the earth, descend to the depth of one hundred feet, pursue the subterranean from shaft to shaft, ‘tis the work of man, hither has he traced the glittering dust, and in its pursuit penetrated the bowels of the earth, excavating passages in every conceivable direction. And all this has been accomplished in the space of one short year.”

The environmental degradation that Sawyer witnessed was accomplished with picks, shovels, pry-bars, saws and sluices. The hydraulic process, which is far more efficient, would not be developed until 1853. It too, originated in Nevada City. Sawyer, in his 1884 landmark decision, defined hydraulic mining this way,

“The hydraulic”, as the miners called it, came just in time because the gold rush (1849-1854) was winding down. A population of over 250,000 was realized in 1852, which was also the year of peak production at $81 million. But the era of easy pickings was definitely over. Volume steadily declined after 1853 and so did average daily earnings. This was especially hard on the small independent “companies” whose members split the take. They were forced, in most cases, to abandon their semi-socialist ways to become wage earners. Hydraulic mining, together with quartz mining, revived the declining California gold industry and set in motion the second major era of mining activity that, in terms of duration, industrial construction and gold produced, surpassed the early gold rush period. Keep in mind that the gold rush lasted five or so years while hydraulic mining reigned for about thirty years.

|

| Unidentified Diggings Andrew J. Russell. Photographer for Southern Pacific Railroad |

Gold rushes end not necessarily when the gold runs out, but when the gold becomes less accessible and major companies employing wage labor totally dominate what happens next. This is a pattern that became commonplace in the hydraulic mining industry. Commercial banks were not really needed until the arrival of Comstock silver wealth (1859), which virtually demanded financial institutions whose primary function was extending credit to businesses. Consequently, state laws were amended. In 1862, incorporated commercial banks came into existence paving the way for foreign as well as domestic investment in hydraulic mining, particularly in the 1870s when hydraulic mining accelerated and extended its scope. The vast infrastructure of dams, flumes, and reservoirs requiring ever-increasing investment for growth, was provided by investors in San Francisco, New York and London. Distant investors had no interest in the problems that they were increasingly creating for people and ecosystems downstream.

After the Civil War came an era of technological vision and innovation. The promise of wealth attracted young, intelligent and energetic engineers and mine managers with the gumption and daring to try new things. Innovations included the undercurrent, the inverted siphon and the hydraulic elevator, to name but a few. The mining conglomerates with their own water conveyance systems became proficient at dam building and transport with numerous ditches, flumes and reservoirs including the 80-mile long Milton Ditch. At the Malakoff Mine near North Bloomfield a single monitor (water cannon) with an eight-inch nozzle could deliver 16,000 gallons of water a minute. It could tear away 4,000 cubic yards of earth from the hillside every day.

Efficient engineering meant more effective earth moving and an increased volume of mine waste in the form of boulders, cobbles, sand, mud and contaminates. This productivity was at the expense of plant, animal and human habitat and contributed to the overall ecocide of the native Nisenan people caused by gold mining. Lorenzo Sawyer, when he was a gold miner, commented that “mountains themselves are removed”, while journalist, Bayard Taylor, wrote that in North San Juan he saw, “the very heart of a mountain removed”. Oustamah Hill, Pontiac Hill and other hills were eradicated in Nevada City, while at North Bloomfield most of Virgin Valley was washed away. The Bear River and its tributaries, Greenhorn and Steephollow Creeks, were choked with gravel and contaminants and remain so today.

|

| You Bet Diggings |

The Yuba and Bear River watersheds suffered the most damage. In Nevada County the greatest density of hydraulic mines was on the San Juan Ridge, including the Malakoff Mine at North Bloomfield. To the north, in Sierra County, the highest concentration of hydraulic mining was in the drainages of Canyon and Slate Creeks, both tributaries of the North Yuba. Mining communities like Poker Flat, Poverty Hill, Port Wine, Saint Louis, Brandy City, Gibsonville, Whisky Diggings, Fair Play and others did not have extensive water conveyance systems but their production between 1855 and 1883 was in excess of $60,000,000.

A series of winters with heavy precipitation brought the problems created by hydraulic mining into sharp focus. The flood of 1861-62 is still the most extreme on record and alarmed the farmers and land owners of Marysville because it released all the mining debris that had accumulated on the banks and in the beds of the hundreds of tributaries where miners had disposed of their industrial waste. Marysville, located in the Sacramento Valley where the Yuba River joins the Feather River, responded to continually rising stream beds by constructing levees in 1868, but despite their efforts the town was flooded in 1875. Sacramento, the state capital, was flooded in 1878 and 1881 creating even more awareness of the debris problem.

|

| Remains of a sluice buried under gravel on Greenhorn Creek |

Although hydraulic mining has ended we are still coping with the contamination of the debris and water quality by mercury, arsenic and other hazards. These issues were of no concern in the 19th century, mercury, or quicksilver, was essential to the recovery of gold and was lavishly used in sluices. It was an expense for miners, so they tried to conserve it, but a huge amount got away and much of it is still with us today. The Blue Lead Mine, near Smartsville, in 1866, used three tons of mercury in four miles of sluices A decade later the North Bloomfield Company lost 21,512 pounds of Mercury between 1876 and 1881. (Mercury contamination is not the focus of this piece. See Fraser Shilling’s, Mercury Contamination in the Yuba and Bear River Watersheds. https://cdn-60719434c1ac183a8cdbec26.closte.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/wquality_Shilling_2001_mercurycontaminationintheyubaandbearwatersheds.pdf).

When the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, it transported California’s agricultural bounty eastward and during the 1870s agriculture replaced mining as the leading sector of the state’s economy. By late in the decade the annual value of the dry-farmed wheat crop alone reached $40 million, more than double that of the dwindling gold output.

After a decade of contentious litigation between agricultural interests in the Sacramento Valley and the mining interests in the mountains one case, Woodruff v. North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Co., was gaining traction. The suit was complex and drawn-out with proceedings occurring over several years involving 200 witnesses and 200,000 pages of testimony. According to the evidence presented, over 100,000,000 of cubic yards had been washed (sluiced) by the hydraulic process, and the debris (mine waste) was deposited in the Yuba River and its tributaries. Another 700,000,000 cubic yards remained. In 1883 an estimated 15,000 acres, or an area twelve miles-long, along the Yuba River, by two miles-wide, had already been buried or destroyed.

|

| Hirschmans Diggings, Nevada City, CA Courtesy of the Nevada County Historical Society |

But there’s no controlling the weather. The winter beginning in January 1881, saw a succession of storms unload on northern California. By early February flooding was extensive and, according to the Marysville Appeal and the Sacramento Bee, it was the most devastating ever. The flood control system had clearly failed. Furious and frustrated, farmers and townspeople revived their objections with renewed vigor, hydraulic mining had to be abolished – no compromise was possible.

|

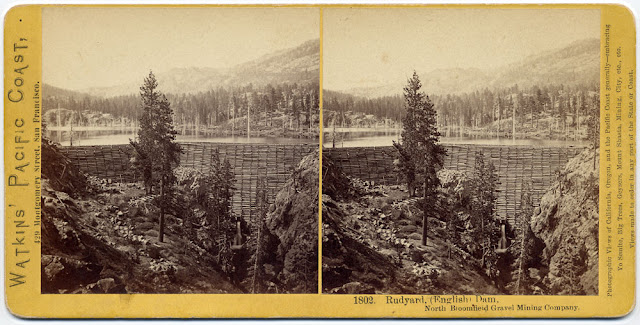

| A stereo photo set of the Rudyard, or English, Dam, 1871 Carlton Watkins |

But the flood with the most long-lasting repercussions occurred on June 18, 1883 when the English Dam on the Middle Yuba River burst. It wiped out every bridge crossing from the dam to Marysville, destroyed every stream-side mining operation, several men lost their lives and, because it was the source of the Milton Ditch, shut down hydraulic mines at Badger Hill, Manzanita Hill, Birchville and French Corral, putting about 100 men out of work. H. C. Perkins, supervisor of the North Bloomfield and the Milton Companies claimed it was sabotage, which was never proven, and posted a $5,000 reward. Sacramento Valley residents claimed the dam was over-topped and incapable of capturing the seasonal snowmelt. Regardless of the reason, the English Dam break affected the Sawyer Decision.

|

| Tail sluices dumping into the Yuba River near Timbuctoo Bend. Men are unloading wood blocks used as riffles in the sluices. Photo by Lawrence & Houseworth, 1867 |

On Jan 7, 1884 Judge Sawyer delivered his precedent setting perpetual injunction. The hydraulic mining companies, “their servants, agents and employees, are perpetually enjoined and restrained from discharging or dumping into the Yuba River, or any of its forks or branches …tailings, cobble stones, gravel, sand, clay or refuse matter.” The debris, the flooding, which reduced navigability of waterways, and the tax burden created by the expense of the levees, left the court with little choice but to enforce the rights of the downstream landowners.

|

| Ferdinand Hauss, Orchardist, Yuba City Photo courtesy of Sutter County Museum |

Judge Sawyer felt that the community had a right to demand that the general welfare take precedence over the unrestrained use of private property. But was it really environmental legislation? The Yuba River as an ecosystem, with its fisheries, plants and animals, was never directly addressed. California at the time of Woodruff vs. North Bloomfield was a battleground for two conflicting modes of capitalist production, gold mining and agriculture or, “Gold vs. Grain”. At the time what conservation consciousness existed was focused on destructive and irresponsible forestry and grazing practices and the creation of forest reserves.

In retrospect, the eventual restraining of mining activities, while it had environmental benefits, did not come from an environmental impulse, nor was the environment its focus. The same lack of attachment to place, the same lack of community, the same short-sightedness, and the same obsession with profit characterized both mining and agriculture. While this important legislation restrained lassie faire capitalism it’s a stretch to call it environmental, but it is a big step in that direction. Following upon the Sawyer Decision was the Rivers and Harbors Act, aka the Refuse Act (1899), which criminalized the dumping of “any refuse matter of any kind” in navigable waterways. Later, in the 1960s and 1970s, when significant environmental law was being crafted, the Refuse Act was evoked frequently to point out injurious conduct.

Miners had complete disregard or lack of awareness regarding the biota or landscape downstream, with small farmers and landowners suffering the (financial) consequences. By the time that the Anti-Debris Association was formed large-scale commercial farmers were involved. They were influenced by one of the largest and most efficient engines of economic development in California, the Southern Pacific Railroad owned by Charles Crocker, Mark Hopkins, Collis Huntington, and Leland Stanford. The “Big Four”, as they were known, had already decided that California’s economic future was in agriculture rather than mining. By the latter decades of the nineteenth century food production was becoming a capital intensive, highly mechanized industry itself, much in the same way that mining had.

After the Sawyer Decision, when wheat farming began to replace mining as California’s primary industry, it too was ecologically transformative as native grasslands and wetlands in the Sacramento Valley were transformed into agricultural fields. Rodman Paul, one of the leading historians of the California gold mining era, observed that, "agrarian frontiers shared with the mining frontiers a persistent American restlessness, an equally pervasive addiction to speculation and a desire to exploit virgin natural resources under conditions of maximum freedom. (Mining Frontiers of the Far West).”

In 1891 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers conducted a year-long investigation of the California debris problem and recommended to Congress that hydraulic operations be allowed to resume if adequate restraining works first were constructed. The idea was to restrain the debris behind dams. A hopeful stance, at best. Once again engineers insisted that it would work, and the state legislators were complicit, if not behind it, because they wanted the money that hydraulic mining generated.

Despite desperate measures to resuscitate hydraulic mining the heavy snows of the early 1890s destroyed many miles of flume and ditch which, with the investors scared off, would not be rebuilt. Chinese miners who leased the Omega hydraulic mine in the 1890s built a debris dam on Scotchman’s Creek, a tributary of the South Yuba River. It was enthusiastically approved by an inspector for the Debris Commission who called it “the best in the state”, but it burst in January of 1896 releasing 100,000 cubic yards into the river, while killing three men.

A few small mines in the Yuba River watershed, like Relief Hill and Jouberts Diggings, were able to limp along but the infrastructure of dams, reservoirs, ditches and flumes continued to deteriorate due to lack of maintenance. It had become obvious that there would be no revival of the glory days of hydraulic mining. This era represents the beginning of statewide water management in California.

Hydraulic mining yielded several billion dollars in gold. But it also produced a debris flow of tidal wave proportions burying thousands of acres of farmland under infertile mud, sand and cobbles. The legacy of hydraulic mining is profound, transforming the landscape by processes that are geologic in nature and scope.

|

| Middle Yuba tailings |

Additional reading:

Beesley, David. Crow’s Range: An Environmental History of the Sierra Nevada. (University of Nevada Press. Reno, 2004).

Greenland, Powell. Hydraulic Mining in California: A Tarnished Legacy. (Spokane, The Arthur H. Clark Company, 2001)

Hagwood, Joseph. The California Debris Commission: A History. Army Corps of Engineers. (Sacramento 1981).

Kelley, Robert L. Gold vs. Grain: The Hydraulic Mining Controversy in California's Sacramento Valley (Glendale, Calif.: A. H. Clark, 1959).

Sawyer, Lorenzo. Way Sketches: Containing Incidents of Travel Across the Plains from St. Joseph to California in 1850, with Letters Describing Life and Conditions in the Gold Region. (New York: Edward Eberstadt. 1926).

Vigars, Kaitlin N., Buried Beneath the Legislation It Gave Rise to: The Significance of Woodruff v. North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Co., 43 B.C. Envtl. Aff. L. Rev. 235 (2016), https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/ealr/vol43/iss1/10